In Light of Change has put additional focus on the events of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this session, we are joined by Dr. Michael Wilson of the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Wilson studies the end-of-life experience of care in the ICU and has augmented his focus in response to the unique needs and circumstances that have been brought to light by COVID-19.

Topics discussed include:

- Factors to consider when facilitating conversations between patients and family members when someone is critically ill

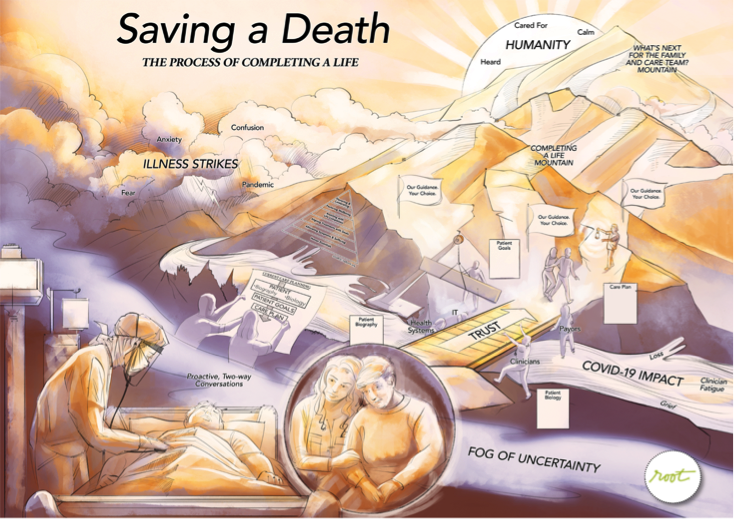

- How a patient’s biology and biography are both necessary parts of their story

- Considering what a good death looks or feels like

- Approaching “saving a death” versus “saving a life” with a focus on measurement and shared success

- Leaders’ roles in enabling change

These issues are being considered in hundreds, if not thousands, of ICU and hospital rooms throughout the country. The full audio interview is available here.

The Conversation

Dr. Wilson is a pulmonary critical care physician in the intensive care unit at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where he cares for patients with a wide variety of illnesses requiring life support and their families.

Dr. Wilson is also a health services researcher and studies the science of decision-making, prognostication, and communication. He tries to examine ways clinicians can improve how care is delivered to ICU patients at the most vulnerable point in their lives, while communicating with them and their family about what’s going to happen. This passion has come from being present at the “fork in the road” between life and death for many patients.

I am a patient and have presented with symptoms of COVID-19, and one way or another, you and I meet. It’s late at night. I’m about to go on a ventilator. What is the conversation you would have with my significant other?

I first try to have a conversation with you, as a patient, if you were alert and interactive enough, which many people are before they go on a ventilator. I would also invite your significant other or family member to the bedside and try to have this conversation together.

If I were just speaking to your significant other, I would say, “Here’s the situation. Your loved one’s about to go on a ventilator. Here’s what’s going on with their body. Here’s what’s going on with their lungs and their breathing. Here’s what the cause of this is. Here’s what the treatments are.”

I would explain what the future might look like, what the pathway forward is. I would explain the procedure – each step of the intubation process. I would explain how we hope the patient would only need the assistance of this breathing machine for a period of a few days, but sometimes people need it for a longer period of time.

I also talk about the path forward. How as the patient wakes up, they may wake up with a tube in their mouth. They won’t be able to talk and they may be confused; they may experience discomfort at that time. And I would assure them that we would be with their loved one the entire time, and do everything for them, the best that we know how, as if they were one of our own family members.

I then acknowledge the uncertainty – that given all of my experience and expertise, having treated similar patients with similar circumstances, I can predict what the next few days will look like, but sometimes I can be wrong. There can be unexpected bumps in the road. And so, while I hope that their loved one can make it through, they are very sick and there is a possibility that they will not make it through this experience. And because of that, I always recommend the family member to take a few moments and speak with their loved one, showing support and love. The goal is for the patient to get well, but if they don’t, at least the family members have these moments together. And throughout the scenario, at each step of the way, I would ask them, “Well, what questions do you have? What concerns do you have?”

That’s what that conversation would look like.

Do you believe most clinicians across hospitals and clinical settings, at this moment, are as prepared as they should be to have that same conversation that you just did, particularly as we are navigating the unknown of this pandemic?

As the years go on and as training programs evolve, the ideas of palliative care and communication are integrated into routine medical practice. Hopefully more and more clinicians throughout the world and the United States are able to have these types of conversations with patients and their family members. As we have these conversations, we need to consider how they can go wrong.

One way this conversation can go wrong is if family members and patients do not have time to express love and support to each other. Sometimes a decision to intubate or place a patient on a mechanical ventilator is so rushed that families are rapidly escorted out of the room – because the medical team is trying to save the patient’s life, which is very appropriate. But if by chance this is the last moment the patient is lucid or conscious before an unexpected death, then those final words are stolen from the patient.

Obviously, we don’t want this to be the final conversation. We’re doing everything to save the patient’s life. But sometimes physicians are bad at predicting who’s going to live and who’s going to die. When it’s been studied, it’s a little bit better than a 50/50 chance. So while we may have a really clear vision of what we think and hope is going to happen to the patient, we know it’s possible to be wrong. I’ve seen many patients survive where I thought they would not. You have to acknowledge that you, as a physician, are not in complete control.

What role does family play after that initial conversation in the patient’s experience of care?

As the physician, I’m the medical expert. I need to be able to answer questions like: What is the patient’s diagnosis? What is their prognosis? What treatments do we have? How likely do we think those treatments are to work for this individual patient?

The family is the expert on the humanity of the patient. Who is this patient? What do they have to live for? What is their life story? What is the life journey? Are they still wanting to keep going with their journey? And what type of burden are they willing to accept to keep going through that journey? What are their religious beliefs or moral beliefs, and how do those impact our next steps?

As we care for the patient, we have to be mindful of the medical facts and the human facts. We need teamwork and a shared process between the family and the clinician.

Why do you think these conversations aren’t taking place more often?

For most of my career, I approached the medical world through the lens of a physician. My focus was on the patient’s medical state and the best course of action to help that patient. I wasn’t thinking about things from the patient’s perspective. However, after speaking to hundreds of ICU survivors and hundreds of families whose patients have both lived and died in ICU over the past five years, I’ve been made aware of things I just wasn’t aware of before.

Another reason why these conversations may not happen is clinician workload and burnout. You might have 20 or 30 ICU patients. You’re trying to save many lives at the same point in time. There’s a lot of urgent situations all the time, and because you’re trying to help as many patients as you can, you become detached or depersonalized from individual patient experiences. All your energy and focus is on going from patient to patient to patient. So you lose the lens, the time, the bandwidth, the thought, to be able to address the humanity of the patient, or to really engage with the patients and their family members in this way. You might even perceive having a conversation with the family as too time consuming. And you’re more focused on saving a life than ensuring a family member says a final goodbye because the metrics of your ICU are based on mortality rates, complication rates, etc.

What is the single biggest thing that needs to shift in order for more conversations like this to be happening?

That’s a hard question. My gut instinct is to say awareness. If we can help health systems become aware how essential these human conversations are, then we can increase the frequency of these conversations. Usually these conversations don’t take more than just a few minutes, but it does take a conscious effort to make it happen.

For example, at our hospital, we have an intubation checklist. Before we intubate somebody, we need to make sure we have the oxygen turned up, we have the correct equipment, that the patient is okay with intubation, that the patients aren’t allergic to the medications and that we’ve dosed the medications right, that they have an IV. There are 15 or so things we methodically go through before concluding that we have done all we can to make the process of intubation safer.

But, perhaps we have not said, “Have I facilitated a conversation between the patient and their family members?” We could make a difference by simply adding to our checklist. Also, this is a behavior we can learn after seeing others demonstrate it. It was really modeled for me by Dr. Sam Brown, an attending physician in the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah. He was able to model this for me, and then I was able to go and do it. I fumbled my way through the first conversations, but then it became easier to facilitate these types of experiences. Now, many nurses have seen me having these types of conversations, and so the nurses start facilitating these conversations because they know it is part of the process.

What is different in a pandemic, specifically in a hotspot for COVID-19?

I think what is different in this era of COVID is the family members usually are not in the hospital because of hospital policies and visitor restrictions. Family members – the experts in the humanity of the patient – are not there. Second is that the workload is increased and the acuity of the critical care patient population has increased. Patients are sicker. More patients are on ventilators. More people are dying in the hospital and in the intensive care unit. There is a component also of this whole scenario about PPE, or personal protective equipment, and healthcare providers and clinicians, nurses wanting to protect themselves against infection from COVID, because we’ve had many colleagues who have been infected or even died from COVID.

Along with increased workload, there’s probably increased stress and increased burnout. And since this is a new disease entity, we’re learning new medical facts all the time about COVID-19 – how it operates and how people progress through it. So our ability to prognosticate what happens to individual patients is evolving over time. All of these factors make it just a little more difficult to help patients and engage patients and families through this vulnerable moment in their lives.

Thank you – you’ve done an excellent job of just describing thoroughly what we would call that current state. Yet when we think about describing success, we typically have metrics, right? There doesn’t seem to be a metric for saving a death. How would you describe what success looks like toward that aim?

One way to look at that is to go back to a patient and the family members. You could imagine for yourself, what would the “ideal death” look like? Some things to consider would be: Did I have good medical treatment? Were the right types of treatments available to me to try to save my life, if it could be saved? Did people do what they could do to try to save my life?

Now if that component has been met, and I got good medical care but I died, what other aspects of death are important? You’d ask questions like: Was I comfortable? Did I die in extreme pain, extreme shortness of breath? Or, did I die “peacefully” and have my symptoms managed, my shortness of breath, my pain, my nausea, etc.?

Then you can look at things unique to the patient, like: Was I able to arrange my affairs, my will, my funeral before I died? Were my religious beliefs taken into consideration? Was I able to say goodbye to people who I wanted to say goodbye to? Was my family comforted? Did my family perceive that this was a comfortable process that was guided by people who cared?

To me these are the core components of what it looks like to “save a death.” How to measure this is quite complicated. But that would be one thing looking towards the future. How can we achieve that?

In closing, as we begin to shift our thinking toward what success looks like, is there anything you would advise for system leaders to be thinking or doing as we move forward together?

My advice for leaders is to look at the macro, but also look at the micro. If I could do anything for a group of leaders, it would be to select five patients and their family members and have them share, in five minutes or less, their experience of being in the intensive care unit, both surviving and/or dying. Because that’s what has changed me; that has blown my mind. I live in the ICU, I work in the ICU. That’s my thing. But seeing and hearing patients and their family members has completely changed how I think about what’s important in critical illness. I understand how this is the worst day of their lives. But for me, it’s just another day at work. I now try to keep this thought at the forefront throughout my “workday.”

I also would advise leaders to take the experience and perspective of individual clinicians who are doing this day in and day out. The people on the frontline are doing their best, but if they burn out, there will be many ramifications for the whole system and patients and family members.

Thank you so very much for your perspective, your expertise, your experience. We appreciate your time and all the work that you’re doing.

If I may add one more thing: I am so humbled by all of the experiences that I read about in the newspaper and I hear from my colleagues. Throughout the intensive care units and hospitals, throughout the world, there are incredible acts of kindness in the hospital and outside of the hospital going on. It’s a tribute to all of the nurses, the administrators, the clinicians, the respiratory therapists, the phlebotomists, the radiology techs, the janitors, family members – everyone coming together to spark humanity in these very, very difficult and uncertain times. I remain incredibly humbled at all of these acts of kindness. And I think we just have so much to learn from each other.

Help Build the Movement

This Root Health conversation is part of an ongoing series on the end-of-life experience of care. If you would like to explore more insights from Dr. Wilson and 10 of the largest leading health systems in the U.S. from their virtual roundtable dialogue, as well as how you can start more of these conversations in your organization, please reach out to Philip Clothiaux at pclothiaux@rootinc.com.